The conceptualization of sex versus gender or what makes a woman, man, or non-binary person is complex, contested, interesting, and important. Kind, reasonable people can hold a diversity of opinions on these issues and still be supportive of transgender people as individuals and a group. Specifically, people can disagree about the nature of sex and gender while still agreeing on dignity and equal humanity of transgender people. I believe that all individuals have the right to live meaningful lives, to be treated with dignity and respect, and to have social supports and resources necessary for safety and well-being (shelter, healthcare, food, employment). The issues at hand involve adjudicating between the competing rights claims and needs of two distinct (and overlapping) groups, females and transgender people. As I noted in the paper, my goal was to expand discussion around these issues, especially scrutiny around the sweeping changes proposed in the US Equality Act 2019 from a particular feminist standpoint. These FAQs are presented to further that discussion in the form of clarification and elaboration.

Link to article here.

FAQs for Scrutinizing the Equality Act 2019

- You argue that laws and social policies need to clearly and consistently distinguish sex from gender. Is this necessary and, if so, why?

- You claim to be pro-sex-based rights. Does this mean you are a ‘gender bioessentialist’?

- In endorsing the notion that sex exists, all going well, in male and female forms, are you ignoring the existence of DSD/intersex conditions?

- Is your defense of females’ sex-based rights and/or the reality of sex transphobic?

- Are you a ‘TERF’ (trans-exclusionary radical feminist)?

- Are you arguing that transwomen are not women?

- Why do you adopt the traditional definition of women since it excludes transwomen? Shouldn’t you be inclusive?

- Your focus throughout is largely on transwomen instead of transmen. Why? And, how do transmen fit in your critique of the Equality Act and policy suggestions?

- You argue that gender identity is unverifiable and unobservable but so is sexual orientation so why don’t you make that argument? (This paraphrases my understanding of a reviewer comment.)

- Would men really pretend to be women in order to gain access to women’s spaces? Isn’t that a fanciful scenario given the stigma around being transgender? And, does this distract from the violence and murder faced by trans people?

- How this has happened so quickly? Why haven’t we had more public discussion, especially around how these changes may affect female people?

- Are you obsessed with bathrooms? Do you propose that we have state (police) gatekeeping at bathroom entry? Why do you care so much about people’s genitals?

- Is your objection to the Equality Act only concerned with the public accommodations provision?

- Is a concern about the terminological precision of the Equality Act actually a real issue or is it a red herring?

- Is your proposal for third spaces unrealistic and unacceptable given the potential harm to trans people from separate treatment?

- Why didn’t you discuss the Hasenbush et al. (2019) study that purports to show that the passage of anti-discrimination ordinances protecting gender identity does not increase crimes against women in sex-separated spaces? (Warning: long, detailed answer).

- Are you relying on a discursive strategy employed by anti-LGBT activists to raise concerns about safety in bathrooms without recognizing that existing laws already ban bad behavior in sex-separated spaces?

- Could you say more about the immutability of sex?

- What is your response to the argument made by some trans scholar-activists that focusing on biological sex is a means of delegitimating and pathologizing transgender people?

- Does your idea of a separate gender status category reify gender (against the feminist aim of gender abolition)?

- Where can I read the Equality Act and the congressional testimony?

- You claim that the Equality Act’s passing evidenced a lack of due process. But, is it simply that you don’t like the conclusions made by those in power in the House (the Democrats)? (This paraphrases my understanding of a reviewer comment).

- You say you support the Equality Act’s aims but not its form. What specific legal rights for transgender people do you support?

Introduction

This paper addresses a contentious topic: the clash of sex-based and gender-identity based rights and how to balance competing interests between two disadvantaged (and overlapping) groups: females and transgender people. Females compose half of the population and have been historically subjugated (were male property for millennia), still face social disadvantages and violence, and possess different reproductive biology and are responsible for the bulk of the reproductive labor, which shapes life experiences in significant ways (e.g., menstruation is painful and disruptive for many; pregnancy and childbirth are physically demanding and interrupt career trajectories). Transgender people also face unique and overlapping disadvantages and violence, including harassment, discrimination, social misunderstanding and even transphobic/homophobic murder. Both females and trans people deserve protections that facilitate their full participation in social life.

At present, U.S. federal policy does not protect transgender people or LGB people adequately from discrimination. The US Equality Act 2019 is an effort to address this disparate treatment. In my paper, I argue that though its non-discrimination aims are laudable, the form is objectionable, especially the bill’s conflation of sex and gender (identity) and the prioritization of gender self-identification over biological sex. Adopting a feminist perspective, I focus on women’s sex-based rights and consider how these will be affected by the Equality Act, recognizing that this discussion has been overlooked and under-scrutinized, even deemed off limits as transphobic. I do not consider female people to be more worthy of protections than transgender people. Rather, I approach this topic from a particular feminist standpoint as a result of the bill’s disregard for females’ sex-based rights, the lack dialogue about the rights and interests of born females, and the prioritization of trans rights over female rights. Again, my focus on females is not because I think transgender people are not equally worthy of federal non-discrimination protections and policies that facilitate physical safety and psychological well-being (including felt security). I am explicitly for LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination protections and females’ sex-based provisions. Unfortunately, at present, as I discuss in the paper, many (including well-meaning) scholar-activists have censored discussion of this clash of rights as off-limit and transphobic, making one either supportive of transpeople OR supportive of sex-based rights. Believing this is misguided and indefensible, this paper addresses this clash of rights.

As I discuss, in some domains, women are being harassed, threatened, and defamed for insisting that sex is real and female reproductive biology matters (see recent online attacks against JK Rowling). On the other side, some trans people feel that their existence is being questioned and their human rights are under debate. Given this fiery, contested context, my paper has the potential to be misread, misunderstood, and/or (as with all written words) misused. Even though this is not a short paper, there are still many details that I could not fit in the article and added clarifications that may prove to be useful for the reader. In this supplement I provide a more thorough discussion of these details in the form of a FAQs list. These FAQs elaborate topics that I would have liked to discuss with more detail (in a world of no space constraints). Some of these questions (Qs) foresee possible reader questions and a few address questions raised by a reviewer, as I note in what follows.

Let me be clear again: I support human rights for all people. At issue is how to negotiate the competing needs and rights claims of females on the basis of their sex and transgender people on the basis of their gender identities. Sex-based rights are not human rights. I do not presume to have all of the answers, but I submit that not discussing the implications of gender identity legislation for females’ sex-based rights is irresponsible and unwise.

(1) You propose that laws and social policies need to clearly and consistently distinguish sex from gender. Is this necessary and, if so, why?

Yes, distinguishing between sex (as male-female) and gender (as masculinity and femininity) and gender status (as a new legal category to protect transgender people) is absolutely necessary for clarity in the intent of the law, especially to plainly identify the categories of protected persons. As I note in the paper, if we cannot distinguish between sex and gender, we cannot protect sex-based rights.

At present American equality jurisprudence (and much of society) inaccurately uses the terms sex and gender interchangeably; this is confusing and misguided. Whatever conception of gender one adopts, gender is not a synonym for sex or a politically correct term for sex (see Richie 2019). The conflation of distinct terms in legal, social, and academic contexts fosters misunderstanding.

For reasons explained in the paper, I submit that we must protect (legal) sex as biological sex and explicitly say sex (not gender) when we are talking about males or females. The ease with which we are undermining women and girl’s sex-based protections is due, at least in part, to people’s confusion about gender and sex. Sex refers to male and female, whereas gender has various usages that capture social meanings ascribed to males and females (e.g., masculinity and femininity). We have customarily and legally separated various provisions (i.e., prisons, sports, bathrooms, locker rooms, military, awards) by sex not gender for good reasons explained in the paper. To use a specific example, until recently, marriage was prohibited between two people of the same sex not same gender. The law was largely clear on this account, but in recent years, as I noted, some scholar-activists have started to erase the distinction between sex and gender. For example, Westbrook and Schilt (2014) discuss “biology-based accounts of gender” (aka, SEX!!) versus “identity-based accounts” for such provisions as marriage. Such postmodern/queer theory accounts of gender disappear sex. When applied to policy these accounts manifest a fundamental misunderstanding and/or misapplication of the law and obscure the social and theoretical utility of the distinct concept of gender. For example, we all know a very masculine (gender) female (sex) is still appropriately assigned to the female prison. These provisions were designed to be sex not gender separated. Inasmuch as statutes use gender and sex interchangeably, we have no way of identifying the appropriate group (sex-based versus gender-based) that is being protected. For example, one finds this ostensibly unintended conflation of sex and gender in the House Judiciary Report on the Equality Act:

“Indeed, the addition of sex as a protected characteristic under Title VI should be read in light of the way that courts and enforcement agencies have interpreted other legal prohibitions against sex discrimination, including analogous constitutional and statutory provisions, so as to permit gender-specific programming and facilities when they are justified. For example, in United States v. Virginia Military Institute, 518 U.S. 515 (1996), the Supreme Court acknowledged that, while single-sex education may violate the Equal Protection Clause in the absence of a sufficient justification, single-sex education can also provide benefits to some students, particularly where such education serves to remedy past discrimination, and that other sex-specific distinctions may be permissible.” (p.16)

Despite the one (inexplicable or at least unexplained) inclusion of gender, this section seems to defend sex-specific provisions in a bill that undermines those very provisions. The use of ‘gender-specific’ in this section suggests to me a confused use of gender as a synonym for sex[1]. Having watched the full House Judiciary subcommittee meeting video twice, I find myself in agreement with Republicans who suggest that Democrats do not understand the implications of the Equality Act. For example, Rep. Foxx (2019) noted:

“[The Equality Act’s] vague and circular definitions of gender identity will lead only to uncertainty, litigation, and harm to individuals and organizations that will be forced to comply with a law the authors don’t even seem to understand. This is a classic example of passing something now and figuring out what it actually means later. We have been here before. If the Devil is in the details, we are in for a lot of devilish surprises.”

The primary issue, in my view, is this confusion of gender and sex perhaps combined with a misunderstanding of what gender self-identification implies. Directing attention to these issues in order to foster dialogue and clarification is a primary purpose of my paper. That said, I submit that it is absolutely crucial to use the term sex not gender when talking about sex (males and females).

(2) You claim to be pro-sex-based rights. Does this mean you are a ‘gender bioessentialist’?

I am pro-sex-based rights, but I am not a bioessentialist with regard to gender. Recognizing sexual dimorphism in human forms in which each form (males, females) produces one of two gametes necessary for reproduction does not make me a bioessentialist or ‘biological determinist’ but a scientific realist. This recognition of biophysical differences between males and females recognizes two reproductive forms and the different (and unequal) burden of labor in reproduction—nothing more. I am explicitly not suggesting that male people cannot be feminine and express themselves in a way stereotypically associated with adult human females. In fact, I encourage that. Rather, I am saying that one’s presentation and behavior not only do not determine sex, but they need not match sex!

As generally used in this domain, ‘bioessentialism’ refers to the belief that male-female differences in personality and competencies (used to justify the subordination of females) are innate and inevitable. That is, sex determines personality and behavior, such that males are naturally masculine/dominant and women are feminine/submissive, naturalizing women’s subordination and submission to men. Bioessentialist beliefs include the notions that females are unsuited for education, the vote, leadership roles, and males are unsuited for caregiving and nurturing roles. Gender bioessentialist ideas include the view that a woman’s proper place is in the home child-rearing and a man’s proper place is in the economic sphere. I explicitly reject those sexist, antiquated, empirically-unsubstantiated beliefs used to naturalize women’s dependence on men.

The idea that recognizing the existence and significance of biological sex (given women’s different and disproportionate role in reproduction) is bioessentialist seems to be rooted in the erroneous belief that the way to achieve sex equality is to deny any difference between males and females. This is misguided because a) differences do exist and that would amount to a denial of a reality of which we are all well aware, and b) if we deny reproductive sex differences, females’ reproductive burden would still exist but would no longer be acknowledged and protected. Elite female sprinters cannot run as fast as elite male sprinters if they try harder any more than elite male sprinters can get pregnant and grow humans in their bodies if they try harder. Ignoring or denying the reality of sex differences in reproductive biology and females’ reproductive burden does not facilitate female equality. For these reasons, I believe that we must acknowledge the reality of biological sex exists and the significance of female reproductive biology, and such a recognition is not bioessentialist in its traditional and widely accepted usage.

In recent years, some queer theory scholars and trans-activists have started to label the beliefs that sex is biological and that sex is immutable as (bad) ‘biological essentialism’. In my view, applying the label bioessentialism to those beliefs (I would say facts) is a mistake. Under that revised conception, nearly every single scientist would be bioessentialist because scientists routinely recognize sex differences in humans and other sexually reproducing animals without qualification. This expanded usage is not just confusing but problematic because in couching those who recognize the reality of male-female forms as bioessentialist along with those who subscribe to the traditional bioessentialist beliefs that females are naturally submissive and properly subordinated to men obscures significant differences in beliefs, which should be distinguished. An analogy to this situation would be labeling people who recognize the existence of differences in skin pigmentation as white supremacists alongside those who think that people with naturally higher levels of melanin in their skin are biologically inferior. This, like the above sex example, confuses recognition of real biological differences in specific delimited areas as negative value judgments. There is nothing negative about being male or female.

As I explain in the paper, biological sex is real and immutable. This recognition that the human species exists in two forms (with some exceptions due to imperfections in the biophysical processes involved in DNA synthesis, meiosis, and reproduction) for sexual reproduction is not only true, but it is important given the different embodied and social experiences of male and female people historically and around the world today. That does not mean that I wish to accentuate those differences, only that I recognize they exist objectively without value judgment, like skin tone differences among people with different ancestries; (please note I am not suggesting equivalency in the differences between skin tone differences or ethno-racial groups and between sexes). It is not by accident and is certainly not a social construction that female humans have grown and given birth to every living human that has ever existed; our sexually dimorphic reproductive forms and roles in reproduction are unchangeable biological facts characteristic of all mammals.

In sum, I am not ‘gender bioessentialist’ because I do not think biology determines character attributes, personality, or proper social role. Rather, biology determines sex, dividing persons into classes that, all going well, can gestate humans or produce sperm, scientific facts that imply absolutely nothing at all about people’s masculinity or femininity (gender).

(3) In endorsing the notion that sex exists, all going well, in male and female forms, are you ignoring the existence of DSD/intersex conditions?

No, and I discuss this in the paper with some detail. I refer you to the section on biological sex, where I note that in the overwhelming majority of cases, sex determination is unambiguous; where it isn’t, in nearly all cases, individuals are still male or female (though there have been extraordinarily rare cases of sex mosaicism/chimerism)—which we have been able to identify because we understand (enough of) the genetic processes underlying sex determination to understand the ‘errors’ that lead to these conditions. A binary view of sex is robust to the presence of a tiny proportion of individuals who, for various reasons, exhibit variation from the usual functional form or are not easily classified (Del Giudice, 2019).

Importantly, this paper is not about people with DSD/intersex conditions. Whether or how to conceive of sex with regard to DSD/intersex conditions is orthogonal to concerns about transgender issues. People with DSD conditions make up a tiny proportion of the transgender population like the general population. Whether or not sex is properly conceived as binary (I think it is), or more of a spectrum given differences in sexual development, is irrelevant for the positioning of trans people in society and under the law. Most trans people do not have DSD/intersex conditions.

Currently, some individuals with DSD conditions are vocally protesting what they view as a ‘weaponizing’ of DSD/intersex conditions for trans causes (e.g., “as a weapon in pursuit of a political, not scientific, ideology” (Graham, 2019)). Graham (2019) also notes: “Every single intersex organization has been clear that intersex has nothing to do with gender or identity”. The idea that people with DSD conditions are less male or female (as implied by a spectral view of sex), unsexed, or even a different sex is misleading and surely offensive to some people with DSD conditions.

The fact of the matter is that individuals with DSD/intersex conditions exist. We can and have made medical and political changes that facilitate humane, supportive treatment of these conditions without throwing the valid functional binary category of sex out the window. That some people do not experience sexual development without a hitch in no way suggests that the categories of male and female are arbitrary or capricious distinctions, which is why there has never been a case of gay males or lesbians accidentally getting pregnant because they did not use protection. We all know why.

Del Giudice, M. (2019). Measuring sex differences and similarities. Gender and sexuality development: contemporary theory and research. New York, NY: Springer.

Graham, C. (2019, September 12). An open letter to Prof. Alice Roberts on the subject of DSDs and kindness. [Weblog post] Retrieved from: https://mrkhvoice.com/index.php/2019/09/12/an-open-letter-to-prof-alice-roberts-on-the-subject-of-dsds-and-kindness/

(4) Is your defense of females’ sex-based rights and/or the reality of sex transphobic?

Dictionaries define phobia “as a persistent or irrational fear of a group… that leads to a compelling desire to avoid it” (www.dictionary.com). I do not fear, dislike, or think trans people are in any way less than any other human being. The differences between gender critical feminists and trans activists are not rooted in hatred or irrational fear, but in disagreements about the sociopolitical significance of sex and the meaning of gender. Many transgender (some prefer the term transsexual) people agree that sex is real, transwomen are male, and females’ sex-based rights matter (see e.g., Hayton, 2018)).

The idea that recognizing the reality of sex is transphobic is not just misguided but silencing. Labeling something transphobic is used to shut down discussion and fear of the label deters women from discussing issues that are relevant to their lives. One can (and I do) sympathize/empathize/have deep compassion for the suffering of trans people; believe that they should be protected from harassment and discrimination based on their trans status (or gender expression, gender identity); and also recognize that sex is real and matters—that there are important differences between females and transwomen. There is nothing negative or shameful about being a male and transwomen like being a female and a non-trans woman.

As I discuss in the paper, being transgender is not the same as being the other sex, and it is essential that we maintain the distinction between sex and gender and our ability to maintain sex distinctions for medical, legal, and social purposes. It is thus necessary and legitimate, not discriminatory or transphobic, to recognize biological sex and to support females’ sex-based rights (see Lawford-Smith 2019 for a robust justification). The unique lives and experiences of females and transwomen are conflated when we deny the reality of sex and sex differences, and lump them into an inclusive, albeit different, conception of women (see #5 below). Women are in my view properly understood as ‘adult human females’, and transwomen are transwomen and deserve to be treated with dignity and extended full human rights as they are, where equally means given a right to things not set aside for those born female and, hopefully, access to provisions set aside for those who experience the unique reality of being transwomen (and similarly for transmen (see #5 below)).

Being/identifying as (however one experiences it) a transgender person is not something that should be stigmatized or erased. We can and should support trans people without denying biological reality. Historically and cross-culturally, societies that have accommodated gender diverse people have done so in a way that recognizes their unique lived experiences and social position. Treating people equally does not mean ignoring differences or erasing distinctions but to value equally and extend equal opportunities, and in some cases where groups have been disadvantaged, extending unique protections on the basis of those differences to mitigate disadvantages. This is why female provisions remain important and sex must be recognized (Lawford-Smith, 2019). Those who support sex-separated sports do not inherently dislike or fear transwomen but recognize that biological factors disadvantage females, as a class, compared to males, as a class, for biological reasons wholly unrelated to gender (Burt, 2019; Coleman, 2017). That both groups (females, transwomen) have been disadvantaged or stigmatized does not make them the same; no male will have to go to work despite having horrible period cramps, and no female will experience penile erection problems.

Broadly, sexism is not a denial of differences between men and women, it’s adherence to a patriarchal ideology that views women as lesser than men generally rooted in negative, limiting, misguided stereotypes. Likewise, racism is not the belief that people don’t have different skin tones and ancestral backgrounds, it is the ideology that white people are superior to black people, grounded in negative, erroneous stereotypes. Homophobia is not a denial that same-sex attraction exists or a disavowal that same-sex sexual behavior is different from opposite-sex sex, it is the belief that homosexuality is immoral, gross, etc., and homosexuals are sick, deviant, inferior and so on. Similarly, transphobia is instantiated in beliefs that trans people are dangerous, gross, less than, ‘pretenders’, or other negative false stereotypes. Transphobia is not instantiated in beliefs that sex exists in two forms or that sex is immutable and is also not evidenced by acknowledging the dysphoric sex-gender mismatch that many trans people experience.

Quite obviously, one cannot acknowledge gender dysphoria or the unique experiences of transgender people if one cannot acknowledge biological sex. Unfortunately, the term transphobia has been weaponized to shut down a discussion of issues that affect many people, including the dysphoric experiences that some trans people experience, and I believe we must call this out. Yes, there are transphobic people; no, I am not one of them; and I believe it would be a mistake to stretch the term transphobic to non-phobic terrains (a belief in sex) because that increases the likelihood that genuine transphobia will be downplayed even overlooked.

Burt, C. (2019). Sex is not gender and sports are sex separated. Medium, Retrieved from: https://medium.com/@callieburt/sex-is-not-gender-sports-are-sex-separated-76b00db0c398

Coleman, D. L. (2017). Sex in sport. Law & Contemp. Probs., 80, 63.

Lawford-Smith, H. (2019). Women-only spaces and the right to exclude. Manuscript.

(5) Does that mean you are a ‘TERF’ (trans-exclusionary radical feminist)[2]?

My feminism centers female people purposely because feminism is for females. As Allen et al. (2018, p.2) aver: “To say that this makes radical feminism primarily ‘trans[women]-exclusionary’, is thus equivalent to saying that a children-only swimming session is ‘adult-exclusionary. It’s not technically inaccurate, but it’s misleading, and replaces the determination to center the needs of a certain group of people with the determination that the purpose of that centering is to exclude.”

Although my feminism is female-focused, I do not wish to exclude trans people from equal participation in society. I can simultaneously seek to advance the status of female people around the world while also supporting the human rights and dignity of transgender people. As Reilly-Cooper (2015) articulates:

“We can support trans women without denying the rights of biologically female women, or without sacrificing their interests and concerns. Part of a feminist understanding of gender is the realisation that those raised as women from birth are socialised and trained to sacrifice themselves and their needs for others. For this reason, it is a radical and revolutionary act of feminist politics to respect the needs and wishes of those raised as women from birth, and to respect their boundaries and exclusions. One of the fundamental aims of feminism is to fight for women’s right to draw their own boundaries, to be able to exercise control over who they associate with and what form this association takes, and this is necessarily a matter of excluding as well as including people. For that reason, the criticism that feminism is exclusionary is generally misplaced, since one of the things that feminism is striving for is for women’s exclusions to be respected.”

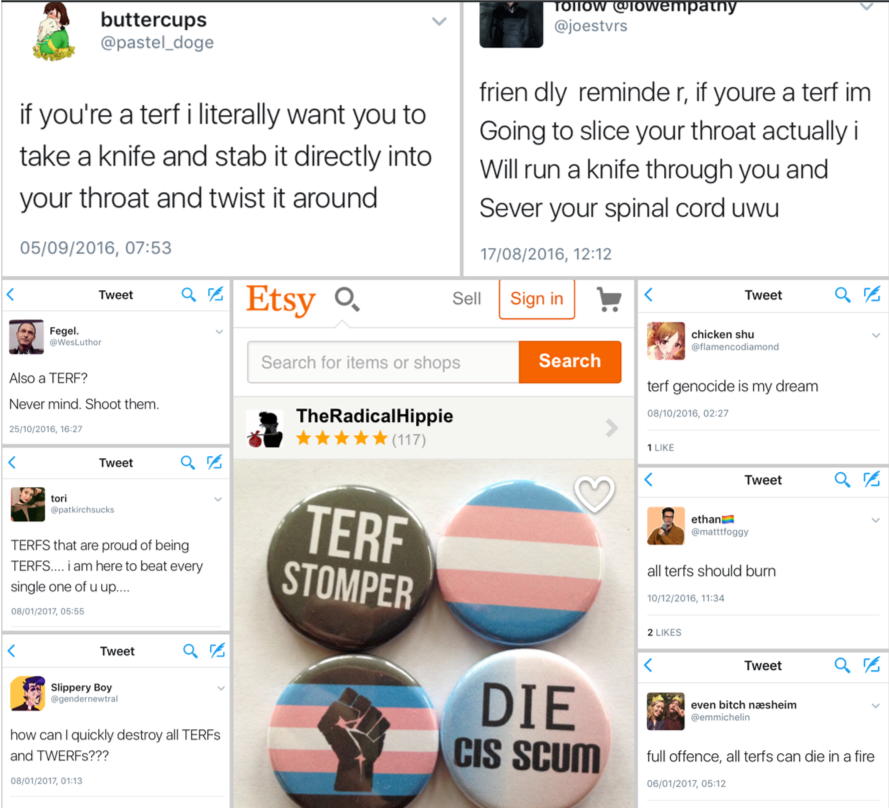

The label ‘TERF’ is misguided and is used as a slur to silence and shame particular feminist women (and a few men) who disagree or question the dominant narrative on trans issues. “While the term ‘TERF’ may indeed have been introduced only as a descriptive phrase to pick out a particular radical feminist position, in its current usage,” as Allen et al. (2018, p.5) note, “the term appears to pick out any individuals, feminist or otherwise, who take it to be politically and socially relevant in certain contexts that transwomen are not biologically female.” The term has been applied to lesbians who profess a belief that sexual orientation is sex-based as well as those who express a concern with the erasure of sex as a political category and a recognition of female biology. As Allen et al. (2018, p.5) articulate: the phrase is not a meaningful description of any feminist politics; it is not accurately applied to a sub-group of people with radical feminist politics; and no feminist describes her own position in this way.” For these reasons, I reject the ‘TERF’ as inaccurate, and I encourage people to recognize the term is a slur and to cease using that term, which is used to shame and silence women who express concerns, a label sometimes accompanied by threats of violence (see the excellent discussion in Allen et al. (2018), and for examples of uses of the term to shame women, see: terfisaslur.com). On the last page of this supplement (see below), I include few random examples taken from the website, these are by no means the worst or the best. (Please note some of these are disturbing with violent imagery, and these are not representative of any group of people, but illustrate the ways in which TERF is being deployed to shame, silence, and intimidate mostly women who express disagreement).

Allen, S. R., Finneron-Burns, E., Leng, M., Lawford-Smith, H., Jones, J. C., Reilly-Cooper, R., & Simpson, R. J. (2019) On an Alleged Case of Propaganda: Reply to McKinnon. PhilArchive: Retrieved from https://philarchive.org/archive/ALLOAA-3

(6) Are you saying transwomen are not women or ‘real women’?

Unequivocally that is not what I am saying. Whether “transwomen are women” or “transwomen are ‘real women’” is not a question I am asking or trying to answer. In my opinion, what makes a man or woman or non-binary person is complicated and interesting. Benevolent, reasonable people can hold divergent views on these issues and still be supportive of transgender people. Trans people themselves hold diverse views on these issues. Whether ‘transwomen are women’ is irrelevant to my foci, which concern practical issues related to the negotiation of rights. Specifically, given that we have sex-separated spaces, how do we accommodate people who identify with/as the opposite sex into spaces separated by sex?

Although out of scope, whether transwomen are properly categorized as ‘women’ depends on one’s definition of woman, a concept whose meaning is currently contested in scholarly (e.g., feminist philosophy, see, e.g., Bogardus, 2019; Byrne, 2019; Jenkins, 2016) and non-scholarly contexts. According to the traditional definition or ‘dominant manifest meaning’ of women as ‘adult human females’ transwomen are not women because they are not female. That, of course, does not mean they are men, or that we shouldn’t refer to transwomen as women. On other definitions, developed in queer theory and feminist philosophy, which engage in what Bogardus calls ‘deliberate conceptual engineering’ as ‘ameliorative inquiry’, a project that involves revising concepts for social justice aims, some transwomen are women and some adult human females are not women (see Haslanger, 2012; Jenkins, 2016).

Again, whether or not transwomen are women is, in my view, irrelevant for the discussion of sex-separated spaces and is not a question I wish to address, as I am neither an expert or authority on womanhood. I adopt the traditional definition of women here, given that it is the ordinary and, I believe, the most useful conception. Adopting this definition does not in any way suggest that transwomen are less than female people nor does it mean to deny their experiences. Rather, it is to adopt a term that identifies a particular class for feminist theorizing and social policy (see Bogardus (2019) and Byrne (2019) for illuminating philosophical discussions of this topic).

Bogardus, T. (2019). Some internal problems with revisionary gender concepts. Philosophia. Online first:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-019-00107-2.

Byrne, A. (2019). Are women adult human females? Philosophical Studies, online first: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01408-8

Haslanger, S. (2012). Resisting Reality: Social Construction and Social Critique. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jenkins, K. (2016). Amelioration and inclusion: Gender identity and the concept of Woman. Ethics, 126, 394–421.

(7) Why do you adopt the traditional definition of women since it excludes transwomen? Shouldn’t you be inclusive?

Concepts are terms with meanings that facilitate communication and shared understanding. Concepts are purposely exclusionary; they highlight specific things with shared properties so that we can identify these things (versus other things) and talk about them. If you tell me you have a kitten, and I come over to find a puppy, I will be baffled. This is not because kittens are better or worse than puppies but because kitten, in our shared language, is widely understood to mean a young feline. We have distinct terms for young dogs and cats because they are different in some significant ways. I believe it is a profound misunderstanding of the purpose of concepts to advocate that their proper aim is wide inclusivity and/or social justice (see Dembroff, 2019; Haslanger, 2012, for different interpretations). The term female, for example, is purposely exclusive of males; that is the point.

I do not adopt the trans-inclusive definition of women because I find the traditional definition to be a good one, and the revised definitions of women all have problems that vitiate their utility. For one, if we redefine woman to include some males, as Byrne (2019), Stock (2019), and Reilly-Cooper (2015) have argued, we are just going to have to come up with another term to mean ‘adult human female’—to pick out that category of humans that may get pregnant; who are not at risk for prostate cancer; and who are at risk of uterine cancer (as most adult human females have a uterus). As Bogardus (2019) explains, the primary reason that these conceptual engineering projects run into problems is that in revising conceptual definitions, these accounts necessarily change the subject (Haslanger (2012) also addresses this issue with her ameliorative project).

Another way to think about the limitations of these ameliorative definitions is to focus on their inclusivity and exclusivity problems. In all revised definitions some adult human females are excluded from the category woman and some people who neither are female nor think of themselves as women would be included as women (e.g., Jenkins, 2016, see discussion in Bogardus, 2019). To use an analogy for illustration, if, in an effort to be widely inclusive, I redefine the term ‘basketball’ to mean all round balls that bounce, I am necessarily changing the subject of basketball (creating a homonym) because some basketballs in the dominant manifest definition do not bounce (a flat basketball; this is the exclusivity problem), and many balls bounce that would not be usefully deemed basketball (think of trying to play with those tiny super bouncing balls; this is the inclusivity problem) (Bogardus, 2019). Not only is that problematic because basketball has a meaning and ‘round ball that bounces’ is not it, but if I were to successfully change the definition of basketball, we would just have to come up with another term for the ‘objects formerly known as basketballs’ to pick out that class of balls that we use to play the game of basketball.

For a defense of the traditional definition of women as ‘adult human females’ see Bogardus (2019) and Byrne (2019). Examples of ameliorative efforts to redefine woman to include transwomen can be found in Jenkins (2016) and Bettcher (2017). It might be noted, although she goes on to reject this definition, Bettcher averred: “On the face of it, the definition ‘female, adult, human being’ really does seem right. Indeed, it seems as perfect a definition as one might have ever wanted” (Bettcher 2009: 105). I concur. Nonfemale people can identify with women, even be referred to as women in certain contexts or situations, but the move to redefine woman to include transwomen either pushes some women out (via new definitions that do not apply to them) or expands the concept so widely that we will have to come up with some other term (‘potential menstruators’) for adult human females, despite having one that exists and that does the job.

Bettcher, T. M. (2009). Trans identities and first-person authority. In L. Shrage (Ed.), You’ve changed: Sex reassignment and personal identity (pp. 98–120). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Bettcher, T. M. (2017). Through the looking glass. In A. Garry, S. J. Khader, & A. Stone (Eds.), The Routledge companion to feminist philosophy (pp. 393–404). New York, NY: Routledge.

Bogardus, T. (2019). Some internal problems with revisionary gender concepts. Philosophia. Online first:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-019-00107-2.

Byrne, A. (2019). Are women adult human females? Philosophical Studies, online first: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01408-8

Dembroff, R. (2019). Real Talk on the Metaphysics of Gender. Forthcoming in Takaoka & Manne (eds.) Gendered Oppression and its Intersections, an issue of Philosophical Topics. https://philpapers.org/archive/DEMRTO-2.pdf

Haslanger, S. (2012). Resisting Reality: Social Construction and Social Critique. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jenkins, K. (2016). Amelioration and inclusion: Gender identity and the concept of Woman. Ethics, 126, 394–421.

(8) Your focus throughout is largely on transwomen instead of transmen. Why? And, how do transmen fit in your critique of the Equality Act and policy suggestions?

My focus is predominantly on transwomen due to the clash of rights between two disadvantaged (protected) categories (females and transwomen) created by the Equality Act. Because male people are not a protected category, extending right-of-access to male provisions to female people solely on the basis of a performative utterance is less of a concern for me as a feminist (in this feminist piece). Moreover, I cannot speak to the experiences of men in terms of their privacy in sex-separated places. I do not wish to continue the pattern of leaving transmen out of the discussion, but there is good reason: men are not a protected category in our society and there is no clash of rights between disadvantaged groups from extending right of access to born females to male spaces.

We provide sex-separated spaces for females for safety, privacy/dignity/comfort, and respite, and as I note in the paper, public sex-separated spaces for females were instituted after feminist campaigns (Carter, 2018). By and large, male people did not fight for their sex-based provisions (their provisions were the default), and as many feminist scholars have noted, the default male has continued to be treated as coextensive with normal human experiences until recently (e.g., crash test dummies, testing medicines, etc.) (e.g., de Beauvoir, 1949; Perez, 2019).

Importantly, female provisions were provided to female people on the basis of their femaleness. The extension of gender self-id right-of-access to male spaces to born females does not undermine special rights extended to a subordinate group or threaten males because, by and large, females are not a physical threat to male people. Thus, while not diminishing the importance of men’s spaces for men’s experiences—whose privacy and dignity matters—I (as a female person in a feminist piece) am not concerned about transmen using men’s provisions (and, frankly, I haven’t seen any men complain about it). Elsewhere I have argued that I would be open to having the men’s provisions the ‘open’ provision with females having a female-only “protected” provision. Again, my feminism centers female people and their concerns from a particular feminist standpoint.

De Beauvoir, S. (1949). The Second Sex: Vintage Books Ed, 1989. Translated and edited by H. M. Parshley, Introduction by D. Bair. New York: Vintage.

Perez, C. C. (2019). Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men. Abrams.

(9) You argue that gender identity is unverifiable and unobservable but so is sexual orientation so why don’t you make that argument? [This question was inspired by this reviewer comment: “Yet, the authors’ bio-determinism with gender is a source of a problem; whereas, the lack of a biological basis of sexual orientation is not a problem. Why?”]

Contrary to the interpretations of a reviewer, to whom I extend thanks for raising this issue so I can clarify, it is not my position that gender identity should not be protected because it is not biological whereas sexual orientation is biological and should be protected on that basis. As I note in the paper (more clearly in this version given the reviewer comments), although I believe the definitional conflation of sex and sexual orientation in the Equality Act is undesirable (because it is inaccurate), whether or not sexual orientation has a biological basis is immaterial. The Equality Act’s redefinition of sexual orientation “is not a problem” because extending anti-discrimination protections to LGB people under ‘sex’ protections does not create a conflict with sex-based rights.

To elaborate further, first, I am not a “bio-determinist with gender”. Sex is biological, but (as I noted in my paper and in #2 above) nothing about how a person should live, love, or behave need flow from the recognition of the facts of biological sex; (ergo, my conception of gender is not properly deemed a ‘bio-determinist’ position).[3]

Second, whether or not some trait or disposition is innate and/or unchangeable is not, in my argument, a reason for extending or withholding rights on the basis of that trait or disposition. Naturalness is not a criterion for political rights. Third, I do not adopt the position in the paper that sexual orientation is biological (in the sense of innate, genetic, and/or congenital). I do not take a position on the cause or basis of sexual orientation. Such a discussion is out of scope; for those interested, see Diamond (2008) for evidence on sexuality fluidity and Walters (2016) for an interrogation of the evidence for a biological basis of sexual orientation.

The etiology of sexual orientation is not relevant to this discussion because I am not making a distinction between ‘biological sex’ and ‘biological sexual orientation’ and ‘non-biological gender identity’. Rather, the definitional conflation of gender identity and sex in the Equality Act is my focus because, whatever gender identity is and however biological, it is not sex, and sex is currently a protected characteristic. Thus, prioritizing gender identity regardless of sex for sex-based provisions undermines sex-based rights (the point of my paper) to the detriment of females. In the fanciful scenario where we were to identify a single biogenetic cause for gender dysphoria or a transgender identity, my position would be the same because regardless of the causes of the identity, experience, or condition, transgender people still have a sex (a reproductive form) and having a biological cause does not make transgender people the opposite sex. Transgender people should be free from harassment or discrimination on the basis of their gender presentation or status. Sex, however, still exists as a separate, protected characteristic.

Diamond, L. M. (2008). Sexual Fluidity: Understanding Women’s Love and Desire. Harvard University Press.

Walters, S. D. (2014). The Tolerance Trap: How God, Genes, and Good Intentions are Sabotaging Gay Equality. NYU Press.

(10) Would men really pretend to be women in order to gain access to women’s spaces? Isn’t that a fanciful scenario given the stigma around being transgender? And, are you overlooking/ distracting from the real violence and murder faced by trans people?

Would men pretend to be women to access women’s spaces? Absolutely yes, they already do. In the past decade see here and here and here and here and here and here and here and here and here for a few examples. Predatory men go to extraordinary lengths to victimize women. For an extreme example of male predatory efforts to gain access to spaces where women are partially nude, check out the Boulder, CO ‘porta-potty-peeper’ who hid in the excrement tank of a porta-potty at an outdoor yoga retreat so he could watch women use the restroom.

As I noted in the paper, it would take an extraordinary amount of willful blindness or naiveté to fail to recognize that predatory males will exploit gender self-id to harm women. They already have. This is not transphobic dog-whistle, which is why Bettcher (2018) a well-known scholar-activist and a transwoman herself, expresses the concern: “Worried about men trying to pass themselves off as women to hurt us? Well, guess what? I’m worried about that too. Even the concern that on-line dating sites for lesbians don’t or won’t provide information about whether a potential date has a penis or a vagina, can be of equal concern (or lack thereof) to both trans and non-trans women alike” (emphasis added).

If the Equality Act passes and it becomes increasingly well known that anyone can gain access to female spaces by self-declaration, then we might expect male predators to feel more emboldened about accessing women’s spaces, recognizing that if challenged, they can claim gender-right-of-access with the standard of proof being “because I said so”. For example, last year, a man who attempted to assault a woman in an Indiana Wal-Mart restroom was found by the police in the electronics department researching ‘transgender bathroom laws’; when caught, he complained to the police about the lack of a separate transgender bathroom (see: https://www.wave3.com/2019/03/25/man-arrested-after-allegedly-inappropriately-grabbing-woman-walmart-restroom/). He was on bond for a prior offense and had possession of meth and syringes, and there was no evidence he was transgender. Of course, even if he was transgender, he assaulted a woman in the restroom; however, under the Equality Act if a person caught him before the assault in the women’s room, he could have claimed that he had a right to be there, and we would be required to take him at his word. (For those interested, he was charged with sexual battery and drug possession.)

To be very clear, I am not suggesting that we will see a spate of attacks immediately following the Equality Act. Rather, I am suggesting that predatory males could be emboldened to use women’s sex-separated spaces as social norms that generally stop most predatory men from entering women’s spaces and give women confidence to challenge and the right to exclude men will be eroded, since physical appearance will no longer provide cues about right of access. Of course, stranger predatory attacks are not an everyday-in-every-locality occurrence, after all, but to suggest that this is a farfetched and unreasonable concern—that this situation is not going to happen—is belied by the fact it already has.

Violence against transwomen is almost exclusively a male problem—male perpetrators and male victims. Females should not have to compromise their safety, dignity, and privacy, opening their spaces up to potentially predatory males to protect transwomen from male violence. Women are not the problem here; males are. As with feelings, one groups’ safety should not be prioritized over the other or compromised when there are alternatives, including third gender-neutral spaces.

Some may still be unconvinced by the idea that predatory men will adopt stigmatized identities to access spaces set aside for vulnerable populations. Research from two incarceration facilities (Riker’s Island and LA County Jail) evidences that even in high-security carceral facilities males will pretend to be gay to gain access to coveted spaces (in this case to be housed with gay men and transwomen). At the LA County Jail, Dolovich (2011, 2012) observed that men pretending to be gay in order to access the special unit was a daily occurrence, even in the face of official gatekeeping (as gay verification policies). Indeed, as Dolovich noted, the failure of gay self-ID as gatekeeping for access to provisions instituted to protect gay and trans persons led to the demise of the Rikers Island special segregation unit operated by the NYC Corrections Department. At Rikers detainees could gain admittance to the gay and trans unit merely by declaring themselves eligible (self-ID), and the result was a mix of “genuinely vulnerable individuals with ‘violence-prone inmates’ who claimed to be gay in order to prey on other residents in the unit” (Dolovich 2012, p.88, citing Zielbauer, 2005). As Dolovich (2012, p.88) notes: “The experience of Rikers is similar to that of LA County’s “homosexual” housing unit prior to the establishment of the gay and transwoman K6G unit and “suggests that the present tight control over admissions is a key component of K6G’s success.”

Dolovich (2011, 2012) documented the gatekeeping processes instituted to maintain the integrity and safety of those in K6G. In order to gain access to the special unit, self-identified gay men have to establish that they are in fact gay (Dolovich 2011). Although some have criticized this gatekeeping process (Richardson 2011) and certainly it is imperfect, as Dolovich (2011, 2012) argued, without gatekeeping, the protections were lost (because predatory males opted in). Thus, consistent with the arguments in the paper and evidence from basically all of human history, evidence from even the highly masculine contexts of male prisons suggests that predatory males will take advantage of self-ID to prey on others. We should expect that right-of-access to women’s provisions on the basis of gender self-ID will also be used by predatory males. When any man can gain access to women’s spaces based only on in-the-moment self-declaration, the result is compromised safety for both women and transwomen.

Finally, to the question of whether the violence and harassment that transwomen suffer is so great that this justifies the compromise of females’ sex-based rights, my answer is simply: no. First, violence against transwomen is terrible, and too many transwomen are harmed by transphobic/homophobic people. However, we cannot say that transwomen suffer more than female people (or vice versa). Females remain harassed, assaulted, raped, and murdered by male people at an unacceptable level. Both groups experience violence at the hands of male persons; neither group can claim ‘more oppression’ justifying the compromise of provisions that will only make women and transwomen less safe from male violence. Most importantly, the idea that transwomen’s suffering justifies their inclusion into female spaces is illogical for all the reasons discussed.

Bettcher, T. M. (2018, May 30). ‘When tables speak’: On the existence of trans philosophy. [Weblog post] Daily Nous. Retrieved from: http://dailynous.com/2018/05/30/tables-speak-existence-trans-philosophy-guest-talia-mae-bettcher/

Dolovich, S. (2011). Strategic segregation in the modern prison. Am. Crim. L. Rev., 48, 1.

Dolovich, S. (2012). Two models of the prison: Accidental humanity and hypermasculinity in the LA County Jail. J. Crim. L. & Criminology, 102, 965.

Robinson, R. K. (2011). Masculinity as prison: Sexual identity, race, and incarceration. Calif. L. Rev., 99, 1309.

Zielbauer, P. V. (2005, December 30). City Prepares to Close Rikers Housing for Gays. New York Times.

(11) How this has happened so quickly? Why haven’t we had more public discussion, especially around how these changes may affect female people?

In the introduction of the paper, I discussed the speed of the trans movement, noting the observations of others that “progress on trans rights has been stunning…. rapid and dramatic” (Taylor et al. 2018). This is no doubt facilitated by our technological advances (internet, social media), which have enabled communication on a scope previously unimaginable. These sociocultural shifts, which involve increased recognition, prioritization, and accommodation of the needs and struggles of trans people in some cases by eliminating the sex-based rights of female people, have surprised many people, myself included. Understanding how a small number of organizations (esp. HRC, but also GLAAD, ACLU) have achieved considerable political, media, and social influence deserves more attention not only for this issue specifically but also for recognizing how powerful influence groups can corrupt democratic policy-making through policy capture (see Blackburn & Murray, 2019, for a discussion in the Scottish context).

While a number of US jurisdictions have increasingly prioritized and passed gender identity legislation (but see Idaho for a recent example of the opposite trend with HB500 and HB509), these laws have, for the most part, been the product of policy capture by trans activists groups without much public discussion. Indeed, it remains the case that we still do not know much about transgender [note, ‘transgenderism’ would be more grammatically pleasing but it is a term that is frowned upon; thus, I do not use it]. For example, explanations for the rapid increases in gender dysphoria referrals and the reverse of the sex-ratio in trans youth (from predominantly males to majority females) are lacking (but see Littman, 2017). Many people are not clear on the distinction between sex and gender; fewer still likely understand that for all the talk about the complexity of biological sex (whether or not it is ‘binary’ or a ‘spectrum’), issues relevant for DSD/intersex conditions, these issues are by and large orthogonal to intersex/DSD conditions. As Jane Clare Jones (2019) averred: “even were sex a spectrum (which it’s not), the existence of green still wouldn’t prove that blue is actually yellow”. Many people likely remain unaware of the distinction between transgender and transsexual, thinking of the latter when discussing the former. However, at present, being transgender has no necessary connection to gender presentation or even sex dysphoria; people who present in stereotypically male ways (as ‘men’) can and do call themselves transwomen and claim eligibility for women’s provisions (see Reilly-Cooper 2015). And, although much is made of the medical support for transgender youth, increasingly medical professionals are expressing public concern about the ‘affirmation only treatment’ given to gender questioning young people, especially those who suffer from emotional trauma, mental illness, and other factors, and in light of the increasing visibility of those who ‘detransition’ (e.g., Bewley et al., 2019). Many people still do not know any trans people, and fewer still have taken the time and effort to develop informed views around how society and the law should evolve around sex and gender.

Despite this lack of understanding and uncertainty in social and medical arenas, how has the trans rights movement managed to gain broad support for the idea of prioritizing sex over gender identity, undermining sex-based rights, and fostering ideas, such as that people have a sexed mind-body mismatch, despite widespread rejection of Cartesian mind-body dualism? A few years removed from the legalization of same-sex marriage and less than two decades after the national legalization of same-sex sex (both via SCOTUS ruling not federal legislation), we now have House passage of an act that institutes sex self-identification regardless of sex, thereby terminating female protections based on sex in favor of those based on gender self-identification, with the very real possibility that if the Senate gains Democratic control in the 2020 elections, this House bill may become federal law?

In the paper, I point to the role of the LGBTQ+ lobby groups in capitalizing on the success of the LGB movement including (I speculated) the collective guilt around prior resistance to LGB equality and a collective fear of repeating the same mistakes (‘being on the wrong side of history’). This has led, in my opinion, to an overcorrection as a suspension of normal consideration and critical thinking and a blanket extension of “human rights” to those in the LGBTQ+ umbrella without cognizing the situation including the differences between sex, sexual orientation, and gender (identity). As Reilly-Cooper (2015) noted, such ‘knee-jerk progressivism’ is due likely to the fact that people’s time is limited and these are complex issues, and as a result, without thinking things through, many people on the left are pushing policies of sex self-ID as ‘human rights’ without recognizing the very basic fact that ‘sex-based rights’ are not ‘human rights’, but rather they are purposely exclusionary of the opposite sex. The result is a curious, though concerning, state of affairs, where people with good intentions adopt a position of moral righteousness and assume those on the other side are haters or idiots and sometimes both. There is, however, so much we don’t know and haven’t worked out, and it is not hateful to have concerns about the erosion of sex-based rights.

Focusing on the Scottish case, Murray and Blackburn (2019) have suggested that the prioritization of trans issues over that of women and others is a clear case of policy capture – defined as the corruption of policy making to serve the interests of a particular minority constituency over the interests of the general public. Scholars have explained that policy capture results from tactics by which powerful social interest groups (here HRC and others) ‘capture’ social policy through knowledge production and dissemination, lobbying, financial donations, and threats of trouble [i.e., boycotts]” (Gurran & Phibbs, 2015: 712). Exploring this issue through the lens of policy capture and focusing on HRC given its role as the most well-funded and influential US LGBTQ+ advocacy organization, we can see how the HRC has coopted normal decision-making processes to prioritize the LGB and, especially, TQ+ populations without input from affected groups. The HRC has managed to capture civil rights policy in three chief ways: 1) direct political lobbying and campaign donations, 2) ‘educational programming’, and 3) corporate influence via ‘threats of trouble’.

Human Rights Campaign’s Policy Capture: A Brief Elaboration

Again, I focus on the HRC here, given it is the most well-funded and influential US LGBTQ+ advocacy and lobby group, and given the fact that its influence on the policy capture in this arena is particularly pronounced. I might note that the HRC has promoted LGB (‘gay rights’) policies that I supported and from which I have personally benefitted (e.g., same-sex marriage). However, the gay rights movement of old is no more. In its place, a well-funded, powerful organization and infrastructure, built around the struggle for LGB rights and consolidated around gay marriage, has been constructed. In the wake of marriage equality, the HRC has a vested interest in maintaining itself (including its well-funded positions—the HRC has at least fifteen staff earning more than $250 thousand dollars per year; the president of HRC earned more than $500k per year) and access to power. Thus, HRC attention has turned to trans activism, despite the fact that the T is not about sexuality (and in some ways trans activism and gender identity ideology undermines LGB activism), such that trans activism is now the primary focus of HRC lobbying and educational efforts. This takes several forms across the three arms of the umbrella group that is HRC.

The HRC is composed of two non-profit organizations (the Human Rights Campaign, an organization that focuses on promoting LGBTQ rights through lobbying Congress and state and local officials, and the HRC Foundation, an organization that focuses on research, advocacy and education) and a political action committee (PAC) (the HRC PAC, a super PAC which supports and opposes political candidates). The HRC, which refers to the umbrella group for all three organizations, reported more than $45 million in revenues in 2018 and $43 million in expenditures (according to IRS filings). Over the past 5 years, and subsequent to marriage equality, the efforts and attention of the HRC has shifted from LGB to trans issues (see Biggs n.d.), and this, specifically, is where policy capture is most clearly manifest.

Policy making in the US is asymmetric—that is, decision-making around legislation is titled toward well-organized and well-funded groups who have access to legislators, have funding to encourage legislators to promote their causes, and have the infrastructure to ‘make trouble’ for those who oppose their aims, including mounting public campaigns, financing opponents, and boycotting locales (see e.g., response to North Carolina’s HB2). The HRC, which is not a democratic organization like unions, wields its power and influence to push forth policies favoring gender identity over sex, without a check on its influence, with millions of dollars from billionaires’ foundations for support for trans activism (e.g., Arcus Foundation, Taiwani Foundation). The HRC not only directly lobbies law makers but also uses its considerable power to influence the social construction of trans rights and the discourse around gender identity as well as possible solutions.[1] Bills like the Equality Act, where little to no efforts were made to consider and negotiate competing sex-based and gender-identity based rights or strategize about ways to protect the rights and dignity of trans people as trans people, result. As noted, this is done by direct lobbying of congresspeople (e.g., on the Equality Act[2]), donations to law makers, and educational programming around these issues—including the key message that gender identity should supersede sex and that sexual orientation and transgender rights are intertwined. The HRC touts its ability to reach millions of people through social media, through its magazines, and other media.

In addition to its influence on congresspeople and its influence on the social discourse through media, the HRC Foundation’s educational programming and Corporate Equality Index (CEI) have had a significant influence on beliefs about gender identity and sex- versus gender identity-based rights. The HRCF’s “Children, Youth, and Families Program” provides training for elementary school teachers about how to teach and talk about gender identity in order to support transgender and non-binary students. Among their goals is to promote “gender inclusive schools through elementary school training” around gender (identity) and sexual orientation. To be sure, although much of this training involves the promotion of benefic traits such as acceptance, empathy, understanding and appreciation of differences, a salient part of this ‘in-depth programming’ (HRC terminology) includes the erasure and or denial of biological sex differences. In practice, this involves the replacement of sex with gender identity (e.g., ‘some girls have penises’); the prohibition of differentiating between biological sex and gender, (including, for example, proscribing comparisons of (biological) females with trans girls); and the inculcation of the idea that sexual orientation refers to gender rather than sex, which has the effect of implying that ‘sex preferences’ are transphobic or exclusionary. The message to lesbians, and others, is that their same- or opposite-sexual orientation is morally reprehensible and bigoted if it excludes trans people based on their sex not their gender identity. This shift is obviously contrary to the extensive prior campaigning of HRC and other LGB groups centered on accepting people’s same-sexual orientations as legitimate and morally and socially acceptable.

Despite the fact that some of their gay and lesbian constituents have been criticized, sometimes harshly, for their sexual orientations by opponents of the acceptability of same-sex sex on one side and trans activists on the other, both GLAAD and HRC continue to prioritize gender identity and trans rights over sex and LGB and females’ sex-based rights. Young lesbian-identified girls and women report pressure even harassment for professing an unwillingness to consider transwomen (most who have male genitalia) as dating partners (e.g., Wild 2019). This pressure on lesbians to date transwomen amounts to a denial of their sexuality. In lock step, LGBT organizations have redefined sexuality as being same-gender based. That lesbians are being labeled bigoted transphobes by some activists for acknowledging their sex-based sexual orientation by LGBT organizations and alleged progressives on the left is almost too absurd to be believed. However, there are many receipts.

For example, Wild’s (2019) survey of (mostly) lesbian women revealed a high prevalence (>50%) of pressure and/or coercion to accept transwomen as lesbian partners. Other surveyed women expressed a fear of verbalizing their desires to keep their women’s only spaces and groups exclusive to females, and Wild (2019) noted that young women appeared particularly vulnerable to these pressures. One respondent noted: “I thought I would be called a transphobe or that it would be wrong of me to turn down a transwomen who wanted to exchange nude pictures”; other young women felt pressured to have sex with transwomen “to prove I am not a TERF” (Wild, 2019, p.22). Many lesbians report no longer feeling welcome in the LGBT community and others have been excluded even ostracized and condemned as transphobes for their same-sex orientations (Wild, 2019). In an almost unbelievable situation, Manchester’s gay village no longer welcomes lesbians unless they accept transwomen as lesbians (Wild 2019). Last year a group of lesbians were refused service at London’s Green Room Bar and had the police called on them during LGBTQ pride because, it was later reported, that these women’s beliefs that lesbians are female (with one wearing a wore a shirt that said “lesbian: a woman who loves other women”) was seen as a threat to the safety and well-being of the patrons of the bar (McManus, 2019). Just so we’re all clear, lesbians who professed a belief that lesbians are homosexual females—the literal dictionary definition of lesbian—were kicked out of a (allegedly) gay-friendly bar for being a threat to the safety of others. Similarly, in March of 2019, a group of four (lesbian) women were asked to leave an advertised ‘inclusive of everyone’ transgender visibility event held by Accenture in London because their presence made a panel member “feel uncomfortable”. The women refused, telling organizers that they had obtained tickets to the open event. Seven police officers then proceeded to forcibly remove the women who refused to comply with their demands to leave—again because their beliefs about sexuality made some people feel unsafe (Tominey, 2019). In hindsight, the event adverts should have said ‘inclusive to anyone who agrees with our beliefs about and revised definitions and concepts around sexuality.’

To be clear, I am in no way saying lesbians cannot or should not consider transwomen as romantic partners nor am I ignoring the fact that some self-identified lesbians do. Rather, I am suggesting that in prioritizing transgender interests that clash with sex-based, those women’s and LGB groups who would normally condemn such behavior as anti-female and/or homophobic are not just allowing it, they are actively supporting it, directly, and indirectly through policies that elide the distinction between sex and gender. The result has been, in my view and in the view of others, effective institutional and policy capture that results in the suspension of due process and thorough public consideration and the suppression of dissent (e.g., Murray & Blackburn, 2019). It appears we are here because well-funded lobby group efforts have managed to effectively influence the media and politicians out of the public’s eye, and now many people are too scared to question these issues for fear of being labeled transphobic bigots (see Stock, 2019). The incredible result is that once again, being openly same-sex attracted is something that can get one kicked out of a bar. And, simply saying that ‘sex is real’ is enough to attract book burnings, sexist slurs, and even violent threats on social media (see responses to JK Rowling’s tweets).

The HRC’s monopoly on leftist public discourse around these issues has been achieved in part through its ‘in-depth programming’ and the asymmetry in information provided by the HRC to policy makers, teachers, parents, and others, including presenting the contested ideas that sex is a spectrum and that trans people are really the opposite sex as ‘the latest science,’ along with educational programming that frames a defense of sex-based rights as bigoted even transphobic. This undergirds a shift to prioritize the needs of trans youth above that of non-trans male and female youth. The HRC notes that roughly half of transgender teens had access to opposite-sex locker rooms in school as a major success, pointing to the distress that some trans youth experience around sexed bathrooms and locker rooms. However, zero attention is paid to the effects of eroding females’ sex-based spaces, competitions, and provisions or the distress that females may have due to males self-IDing into their spaces and competitions. By framing the erosion of sex-based rights as “gender inclusivity,” the effects of ‘gender inclusive’ policies on girls is obscured. Similarly, for prisons; while trans activists organizations highlight the struggles of trans people, especially transwomen who wish to be in the women’s prison, incarcerated women do not have any lobbyists advocating for their rights to single-sex spaces. It should be noted that the issue is not that trans activist groups have well-funded, highly organized lobby groups working on their behalf; rather, it is that decision making processes around these issues are not transparent and our system is vulnerable “to single-minded ideologically-driven lobbying”, but deep pockets make it worse (Murray & Blackburn 2o19).

The HRC Foundation’s other major scheme for inculcating its beliefs and policies consistent with them is the CEI. Started in 2002, the CEI has become a visible way of coercing corporations to adopt policies that protect sexual orientation and gender identity without public discussion. In 2020, 686 businesses earned a 100% score in the CEI, and the key shift was noted to be the ‘wide-scale adoption of transgender-inclusive initiatives’ (p.5). To get full credit on inclusivity, companies are required to include various LGBTQ diversity training programs, including programs produced by HRC such as “Transgender Inclusive in the Workplace: A Toolkit for Employers”, which prioritizes gender identity over sex and promotes the erosion of females’ sex-based protections under the guise of transgender inclusivity.

Importantly, not only are corporations rated for their own policies but to receive full points, they are required to engage in “Three Distinct Efforts of Outreach or Engagement with the Broader LGBTQ Community”, which includes, “philanthropic support of at least one LGBTQ organization or event (e.g.: financial, in kind or pro bono support)” and/or “demonstrated public support for LGBTQ equality under the law through local, state or federal legislation or initiatives.” Such enjoinments are instantiated in HRC’s Business Coalition for the Equality Act, “a group of over 260 leading U.S. employers that support the Equality Act…. Coalition member companies represent nearly every industry, employ over 11.6 million people in the U.S., command over $4.9 trillion in revenue and have operations in all 50 states.”

Recently (in 2016), the CEI regulations were altered to penalize companies who provide any funding “to any [non-religious] organization whose explicit mission included efforts to undermine LGBTQ equality” (p.23). While initially that might seem reasonable even laudable, seen in the light of HRC’s endorsement of gender identity ideology, which views recognizing sex and supporting sex-based rights as ‘anti-trans’, this has serious implications. In effect, this means that any support for organizations promoting women’s sex-based rights will result in penalty. For example, if a company supported the UK LGB Alliance, which is a group for gay and lesbian people focused on sexuality, and which excludes male-born people who identify as lesbian, this would be considered “anti-LGBT” by HRC, despite being explicitly pro-LGB (and not caring about gender one way or the other). The CEI is thus a scheme for inculcating a specific set of policies within large corporations and a public commitment specified by HRC that seek to promote public policies, attitudes and organizational protections around gender identity instead of sex without democratic input.

To give a sense of the extent of their influence, the following is a small selection of the wealthy, influential corporations that scored 100% on the CEI, and so in which gender identity is treated as sex for all purposes: Amazon, Apple, AT&T, UnitedHealth, Chevron, CVS, JPMorgan Chase, Verizon, Walmart (all of which are in the top 20 Fortune 1000). Thus, female workers in these corporations have no right to sex-separated spaces, and male individuals who identify as or with women are counted as women and eligible for awards, recognitions and the like. For example, the recorded ‘highest paid female CEO America’ in 2013 was Martine Rothblatt, a transwoman, who ranked at #10, earning 36 million, a full 24 spots ahead of the first born female (Melissa Mayer of Yahoo at 13 million, see here).

More Evidence on Policy Capture and Asymmetry in Policymaking

Further insight into the strategies employed that contributed to the rapid success of this movement were uncovered in a recent article by James Kirkup (2019); he discusses a report entitled: ‘Only adults? Good practices in legal gender recognition for youth’, which is the work of Dentons, a large law firm, funded by pro-bono work organized by the Thomson Reuters Foundation, an arm of the media giant, and the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Intersex Youth & Student Organisation (IGLYO). The report’s stated purpose is “to help trans groups in several countries bring about changes in the law to allow children to legally change their legal sex without adult approval or the approval of any authorities”. Jónsdóttir (2019, p.9), a contributor to the report states: “Children and teenagers need to be allowed to define themselves however it suits them, both in social and legal terms.” Kirkup (2019) describes this report as “a handbook for lobbying groups that want to remove parental consent over significant aspects of children’s lives. A handbook written by an international law firm and backed by one of the world’s biggest charitable foundations.”

The report encourages several techniques as ‘good practices’ to advance this cause. These include:

- To “[g]et ahead of the government agenda and media story”: “In many of the NGO advocacy campaigns that we studied, there were clear benefits where NGOs managed to get ahead of the government and publish progressive legislative proposal before the government had time to develop their own. …This will give them far greater ability to shape the government agenda and the ultimate proposal than if they intervene after the government has already started to develop its own proposals” (p. 19, emphasis added).

- To “[limit] press coverage and exposure” noting that “many believe that public campaigning has been detrimental to progress….In Ireland, activists have directly lobbied individual politicians and tried to keep press coverage to a minimum …” (p. 20, emphasis added).

- To “[t]ie your campaign to more popular reform”: For example, “[i]n Ireland, Denmark and Norway, changes to the law on legal gender recognition were put through at the same time as other more popular reforms such as marriage equality legislation. This provided a veil of protection, particularly in Ireland, where marriage equality was strongly supported, but gender identity remained a more difficult issue to win public support for.” (p. 20, emphasis added).